GUINEA

“Kim, did you know police in Guinea extort more money from bush taxi drivers when skinny, white boys ride shotgun?”

Our bush taxi driver gunned the engine and screamed at the police. The Guinean police had set up a road block and were fleecing drivers. One policeman—playing the good cop—leaned in my open window, and politely said “bon jour” to our driver, Mohammed.

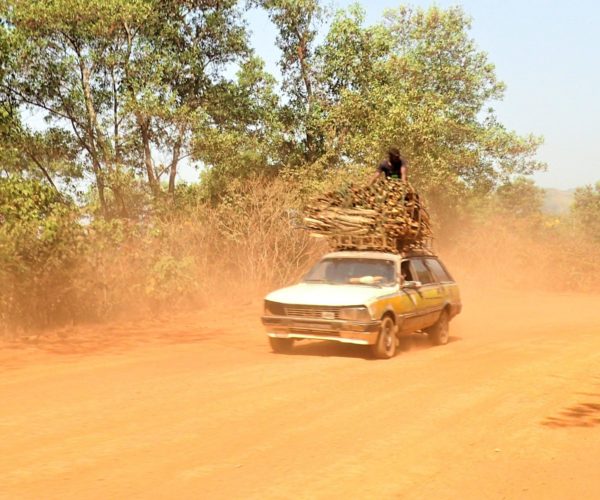

Say what, Kim? What’s a bush taxi?

A bush taxi is a privately-owned car, van, or minibus that makes long distance trips between African cities. Bush taxis don’t have fixed schedules, they depart when all seats have been sold. And if you see a photo of an old Peugeot with loads of stuff tied to the roof—including the kitchen sink—that’s a bush taxi.

I’d been traveling overland through West Africa for two months, and many of my bush taxi drivers were shaken down at police or military checkpoints. It’s part of doing business. But Guinean police are gold-medalists in the extortion game.

We were driving from Guinea’s capital, Conakry, to Freetown, Sierra Leone. A two-hundred-fifty-kilometer-drive that would take us ten, painful hours. Conakry is a complete cluster-phuk; in addition to the hellacious gridlock, the main roads leading into downtown are under construction.

The red clay dust was so thick, street hawkers ran alongside our taxi selling air pollution face masks.

Mohammed was bad-ass. He didn’t take shit—or orders—from anyone, including Conakry’s traffic police. Several times in the crowded roundabouts, Mohammed got the hands up signal to stop. He completely ignored the policemen’s command and slowly drove past saying “ca va” in French.

In this case, ‘ca va’ means “what up, dude … whatcha gonna do?”

And Conakry’s traffic police were no shrinking violets, they carried long, thick rubber hoses to whack disobeying cars! Luckily, we never got a whack job.

Out in the countryside we drove by the first police check point. Mohammed gave a hefty donation to the soldiers’ bribery bank, twenty thousand Guinean francs, or about two dollars.

To put it in perspective, you can get a meal for five thousand francs. So, in the poorest part of the world—according to the United Nation’s Human Development Index (HDI), only five countries are poorer than Guinea—twenty thousand francs is a lot of money.

But shit hit the proverbial fan when we pulled up to the next police check point. Mohammed immediately started screaming. Not yelling. Screaming.

Everyone was screaming! For a second, I really thought Mohammed was going to ram the police barricade. I wanted to record a sound bite of Mohammed cussing out the cops and the engine revving, but the ‘good cop’ leaning in my window could’ve easily snatched my phone.

My fellow passenger Judith—a Sierra Leonean student getting her hotel management degree in Conakry—told me, “don’t give them your passport. The police took my American boyfriend’s passport and demanded one-hundred-fifty-thousand francs.”

I’d already been warned about the passport scam, so I had a photo copy ready. The good-cop asked me for my passport, and I gave him a photo copy.

“Give me your real passport” the policeman said.

“No” I said, looking him straight in the eye with a smile.

The policeman gave up on me and focused on Mohammed. But to my surprise, Mohammed successfully thwarted their extortion attempt, and we finally got back on the road.

“That trouble was all because of you.” Judith said.

“But they’re Americans too” I said pointing at my two fellow countrymen crammed in the back seat.

“Yeah, but you’re white.”

Ouch!

“That trouble was all because of you.”

Nobody in our taxi wanted the white boy to hold up the show again, so Judith said, “walk together with me through the border, so they don’t stop you.”

At West African land borders, the immigration offices are usually just small buildings, with only one or two offices. As a non-African, I always had to go to the top manager’s office to get my passport stamped.

Entering Sierra Leone, there were several local guys sitting in the top dog’s office. As Judith planned, we looked like a couple.

“Is he your husband?” an old man asked Judith in French.

“No, he’s my boyfriend.”

The old man replied “c’est bon” (that’s nice).

But the young guy sitting next to him didn’t think it was nice, and disgustedly repeated “c’est bon?”

As in, c’est bon my ass! He was not diggin’ salt n pepper. Not happy about the tall, skinny, white boy shagging their sister. He gave me a sheepish smile when I glared at him.

I got my passport stamped without any hassle, and I told Judith, “your plan worked, nobody asked me for anything.”

“That’s because you’re not timid” Judith replied.

Hey Kim, isn’t that the understatement of the century!

What blog post category does this tale fit in, Sis? It could go in my ‘travel lowlights’ category, but I had much worse bush taxi rides in West Africa. And when I remember this story, it brings a smile to my face.

White boy riding shotgun causes uproar in Guinea!

Just being in Guinea was a rare experience. Lonely Planet didn’t include any Guinea hostels, restaurants, or reviews in their West Africa guidebook because “very few travelers were heading to Guinea.” So, this Guinea story is not a lowlight.

Calling this story a ‘travel highlight’ might be an exaggeration, but my encounter with pigment prejudice was definitely an eye-opener. Maybe my brief taste of discrimination was some kind of cosmic payback for the white man conquering black Africa.

Yes, you’re right, Kim, our Swedish and Irish ancestors were not big colonizers in Africa. But I’m thinking of the big picture, in a broad perspective.

Maybe I should start a new blog post category for Africa; colonial karma.